What is this?

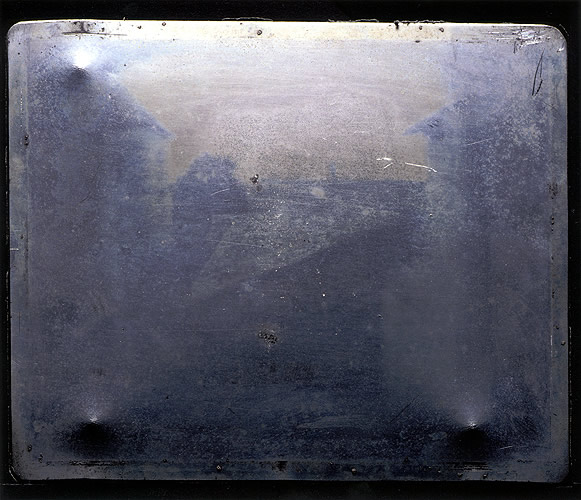

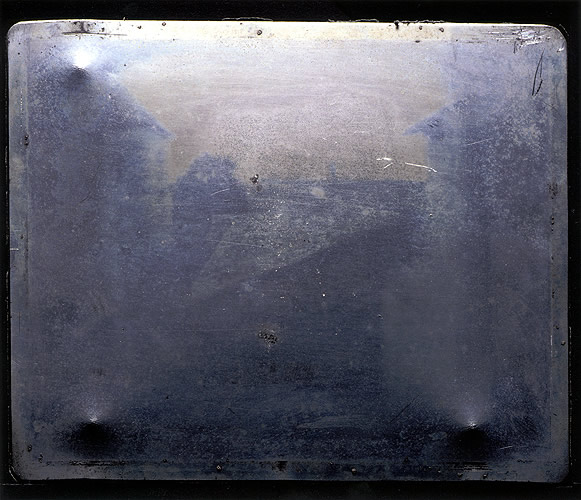

Joseph Nicephore Niepce, View from the Window at Le Gras

c. 1826

This is what is widely considered to be the first photograph (rollover the image to see a gelatin silver print with applied watercolor reproduction from 1952) and it was taken by Joseph Nicephore Niepce in 1826 (click on his name and the title to find out more about both). Niepce, though, didn't call it a photograph, but rather a heliograph, which comes from the Greek helios for sun and graphein for drawing. His choice of words is telling and leads to another question:

Niepce was an inventor who discovered his process of heliography through his interest in another new art form, lithography. Looking to improve upon this printing method, Niepce devised a way of fixing an image. Using materials from the lithography process, he took a pewter plate and coated it with bitumen of Judea, which sounds kind of scary, but is really a form of asphalt. He put this plate in a modified camera obscura and placed the camera on his windowsill; the exposure time was 8 hours. Niepce then developed the plate in oil of lavender and turpentine, which dissolved the undeveloped bitumen of Judea to reveal the image.

Niepce had purchased his camera lenses from Chevalier, an optician in Paris. Chevalier knew of Niepce's experiments and suggested to another of his clients, Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre, that he should get in contact with him because they were both trying to do the same thing: fix an image from nature.

Daguerre is somewhat different than Niepce. Trained as a painter, he was more of a businessman and owned the Diorama in Paris, which was quite successful. The Diorama was set in a theatre and was something like virtual reality for the 19th-century. You would enter the Diorama and watch a country scene, for example, unfold on stage. Through a series of transluscent backgrounds and lighting effects, it would appear that a day would pass, from morning to afternoon to evening; you could experience a day in country while sitting in a theatre in Paris.

Niepce and Daguerre begin a correspondance and eventually form a partnership, Niepce-Daguerre, in 1829, but Niepce dies suddenly from a stroke in 1833. Daguerre cvows to continue their work, but is not having much luck. He can record an image, but he can't fix the image: as soon as he takes the plate out of the camera, the image begins to disappear. One day, after putting away his equipment from what he thought was a failed shoot, Daguerre removed the plates from his camera to find that his images were not disappearing; he had done it, but he didn't know how he had done. He surmised that it must have been something in his storage closet that had reacted with the plates in his camera to fix the image. So, Daguerre went through everything that was there until he found the right combination.

Leonard Francois Berger, Portrait of Joseph Nicephore Niepce

1854

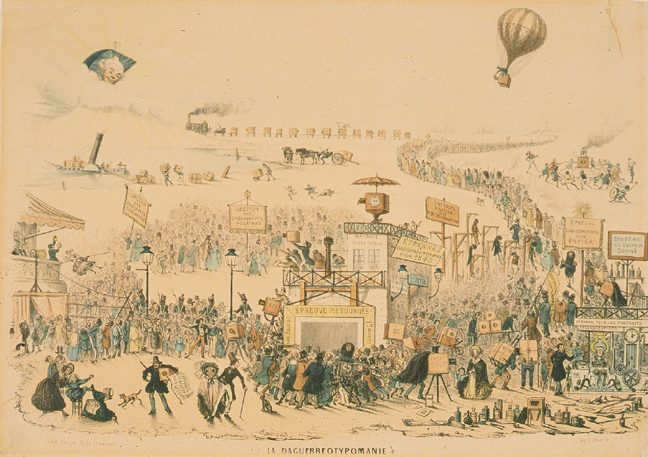

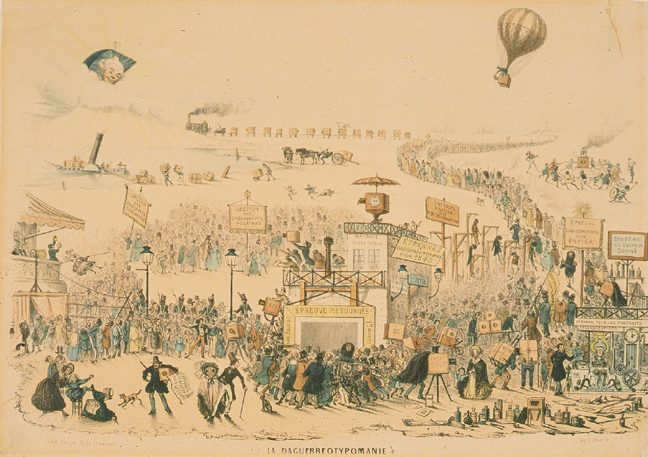

Daguerreotypemania!

Theodore Maurisset, La Daguerreotypomanie

1839

Everyone went crazy for the Daguerreotype. This was the first time that you could accurately record from nature, a mirror of life and (seemingly) objective. Prior to this, if you wanted a portrait of someone, you'd hire a painter to paint it, but how the portrait turned out depended on how good the painter was.

Interestingly, a few weeks after Daguerre's announcement, William Henry Fox Talbot claimed he had invented a similar process.

Daguerreotype camera outfit

c. 1840

Clockwise from left: full plate camera with lens, fuming box (mercury vapor), iodizing box, and plate box

Center: correcting prism

Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre, Still Life or L'Atelier de l'artiste

1837

Daguerre's first Daguerreotype, a still life in his studio, shows the range of tones that could be captured, from black to white. The Daguerreotype is a direct positive, meaning the image appeared as it should, although it is laterally reversed, like looking in a mirror.

HISTORY

There is one thing, above everything else, that we must have to take a photograph. Is it film? Or a lens? Or a camera? Although these things help us take better pictures, there's still something else we need first. Here's the answer, but if you can't see it because it's too dark, rollover below to turn it on ...

Without light, we can't photography anything. Think about it: if I'm in a room with no light and I try to take a pciture, what do I get? Absolutely nothing. It's much the way our eyes work: when light reflects off an object, we can see that object. Niepce, in naming his invention heliograph or "sun drawing", shows how important light is to his process. Again, this leads to another question:

What is the one thing you need to take a photograph?

What was Niepce's process?

What was Daguerre's process?

By 1837, Daguerre had modified Niepce's process, using a copper plate that had been coated in silver and polished to a mirror-like shine. The plate was then exposed to iodine vapors, which formed silver iodine, a light-senstive compound, on the surface of the plate. After exposing in the camera, the plate was developed with mercury vapor, which unfortunately, is highly toxic. When the desired development was reached (known as development by inspection because you would periodically check the plate to see if it was properly developed), the image would be fixed in a salt water bath (sodium thiosulphate or hypo, which is still used today). The result was a direct positive, meaning the image appeared as it should on the plate.

Daguerre continued to perfect his process, which he modestly named the Daguerreotype. In 1839, with the help of his patron Francois Arago, Daguerre annouced his discovery to the Academy of Sciences, giving it to the French government in exchange for a lifetime pension. The government, in turn, then announced the Daguerreotype as France's gift to the world and, from that point on, it was ...

Who is William Henry Fox Talbot?

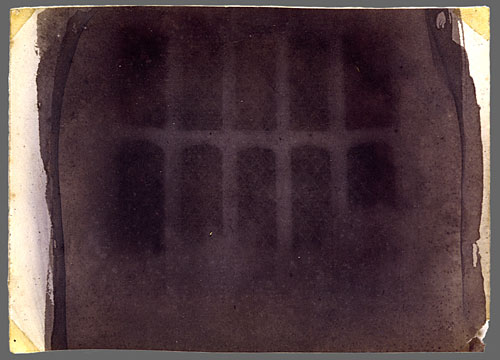

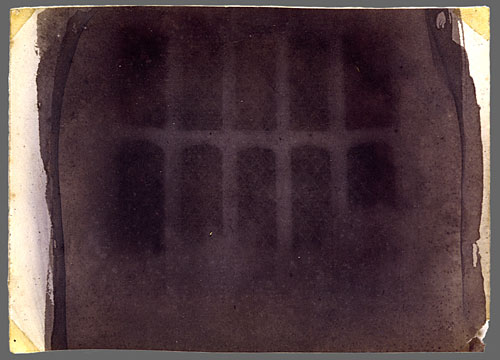

William Henry Fox Talbot, Latticed Window (with the Camera Obscura)

1835

William Henry Fox Talbot came from a wealthy family in England (his family owned a copy of the Magna Carta). Well-educated, he was something of a scientist-inventor, who would wander around the family estate thinking of experiments to do. One such experiment resulted in the image above, which was done about the same time Daguerre was perfecting his process. Talbot pasted the image into one of his notebooks, made some notations, but then moved on to something else, thinking the process was nothing special. But, when he learned of all the attention around the annoucement of the Daguerreotype, Talbot went back to his old notebooks and pronounced that he had invented a similar process, which he called the calotype. Unfortunately, when compared with the sharpness of the Daguerreotype, Talbot's images were, as one of his friend's put it, like scribbles. This was understandable because the calotype process involved taking a piece of paper and soaking it in a silver solution. The paper was then exposed in the camera and, unlike the Daguerreotype which resulted in a direct positive, Talbot's process resulted in a negative. By taking this negative, placing it on another sheet of senstized paper, and exposing it to light, he was able to produce a positive. Since it was derived from a paper negative, the print suppressed detail, but this was one of the things that attracted David Octavious Hill and Robert Adamson to the calotype.

Who are Hill and Adamson?

David Octavious Hill and Robert Adamson, Greyfriars' Churchyard

c. 1845

David Octavious Hill was a painter who was commissioned to paint a large-scale picture, which was to include several hundred portraits, commemorating the founding of the Free Church of Scotland. Instead of having each person sit for a portrait, which would be incredibly time-consuming, Hill decided to photograph each person and then paint the portrait from the photo. Enlisting the help of David Hill, a chemist, they decided to use Talbot's calotype process because it was less expensive and more portable than the Daguerreotype. Additionally, because the prints lacked detail, it allowed Hill more freedom as painter. In addition to these portraits, Hill and Adamson photographed landscapes and locals as well. Since they were working so much with the calotype, they helped to refine Talbot's process.

Eventually, Talbot's negative/positive process becomes the dominant photographic process because it was less expensive and more portable than the Daguerreotype, but more importantly, it allowed for multiple copies of an image to be made from a single negative. The process we use today is a direct descendent of Talbot's calotype.

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Cloisters at Lacock

1844

David Octavious Hill and Robert Adamson, Portrait of Mary & Margaret McCandlish

c. 1845

From paper to glass

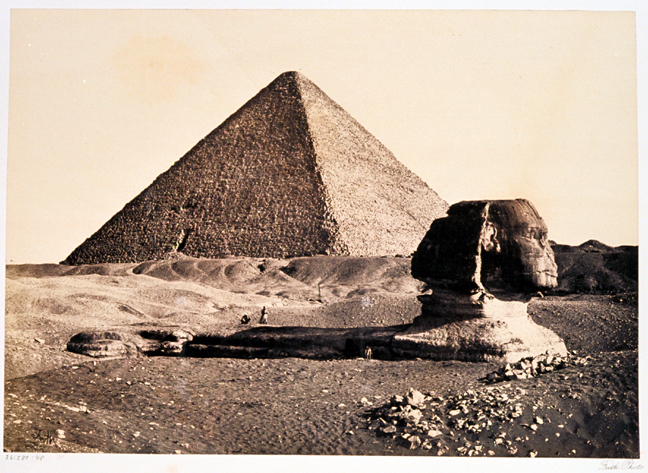

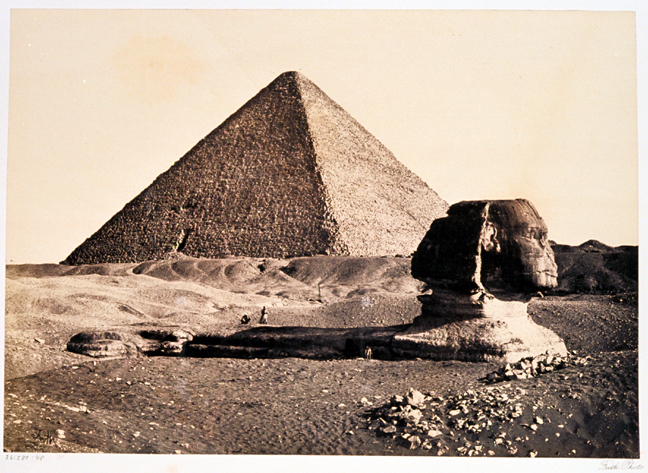

Francis Frith, The Sphynx and the Great Pyramid, Geezeh

c. 1857

One of the problems with the calotype process was the use of paper as a substrate. Regardless of how thin the paper is, there is always texture to it; wax was often applied to paper to make more transparent. Eventually, paper was replaced by glass, but the smoothness of the glass posed a problem because nothing would adhere to it. In 1851, Frederick Scott Archer developed the collodian process which solved this problem. A glass plate was coated with collodian, also known as gun cotton, a mixture of cellulose, ether, and alcohol. The plate was then sensitized in a silver nitrate bath, placed in the camera, the picture taken, and the plate developed. This process is also called wet-plate photography because it has to be done while the plate is wet. When collodian dries, it becomes impermeable (it was used to treat wounds, almost like a liquid bandage). Interestingly, collodian plates could be used as a negative or a positive, if backed by black material (known as an ambrotype). Blackened tin was also used instead of glass to create a tintype, somewhat of an inexpensive Daguerreotype. Collodian plates used as negatives were often printed on albumen paper, which used egg whites as a binder to hold the silver nitrate.

Let's not forget Hippolyte Bayard

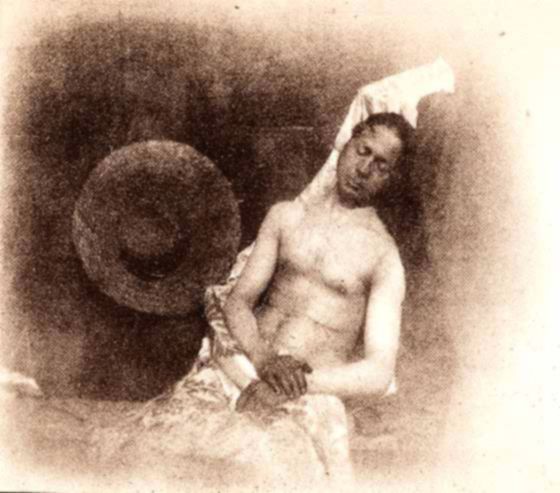

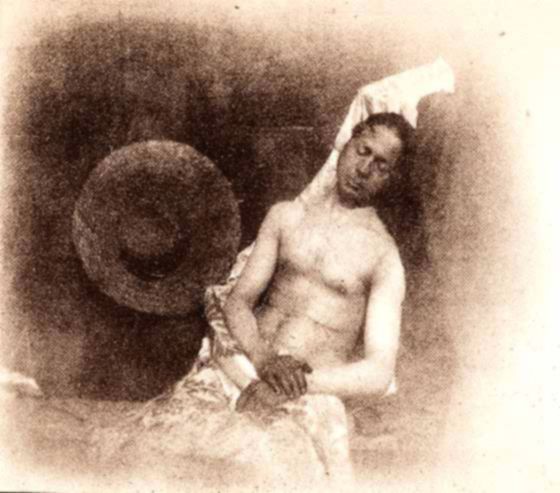

Hippolyte Bayard, Self Portrait as a Drowned Man

1840

It's important to remember that Niepce, Daguerre, and Talbot were not the only people experimenting with fixing an image, one of whom was Hippolyte Bayard. A civil servant in France, Bayard experimented with photographic processes as a hobby and eventually created his own process. He was to announce his discovery at about the same time Daguerre was preparing to announce his, but a friend of Daguerre's persuaded Bayard to wait. When Bayard saw how popular the Daguerreotype was, he felt like he had been cheated and that his process would have been the rival of Daguerre's (it wouldn't have because it had the worst aspects of Daguerre's and Talbot's as a direct positive on paper resulting in a murky image that could not be reproduced). Feeling as though he had committed artistic suicide, Bayard created Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, one of the first examples of conceptual photography, where the idea (or concept) behind the image is overrides the image as document.

On the back of Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, Bayard wrote:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government, which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life...!